Figure 1 Picture credit: Reuters, Victoria Jones/Pool.

Six months on and despite Theresa’s May insistence, nobody really knows what Brexit means. Unsurprisingly, as a leaked memo shows, the government doesn’t know what Brexit means. All that we do know is that we are getting it. For most, Brexit has meant confusion. The concept of democracy has been caught up in this confusing mess. When it comes to the British constitution, Brexit has opened can of worms. Mostly remain representatives were voted into parliament during the 2015 General Election. Yet Britain (England and Wales being the only home nations with majorities) voted for Brexit in 2016. Clearly this is something to do with First Past the Post which fails to proportionately represent public opinion and reduces everything to a two horse race. But it’s more than that. The referendum highlighted how differently we’ve come to use the same word, ‘democracy’, to mean lots of different things on this issue.

Close to home, we’ve seen the rise of direct democracy as a result of the referendum. Having won the referendum, Brexiteers are convinced the people have spoken. All we need to do now is get on with it. They support the Theresa May’s attempt to appeal the Supreme Court’s decision, which, if successful, could allow the government to circumvent a parliamentary vote on activating Article 50. After continually emphasising British parliamentary sovereignty through the slogan ‘Take Back Control’, Brexiteers have come full circle. Now Parliament, chock-full of Remoaners as it is, can’t be trusted to carry through the will of the people. For them, a metropolitan liberal elite with their love of parliamentary procedure and independence of the judiciary, are just getting in the way. The Brexit tabloid press, The Daily Mail, The Sun and The Daily Express have been keen to push this line about a liberal elite as the ‘Enemies of the People’. Nigel Farage has followed suit, his ‘betrayal’ rhetoric comes eerily close to the Nazi’s stab-in-the-back-myth about World War I. Farage is himself an emobodiment of the failure of parliamentary democracy to deal with 21st century politics. He has shown that you can radically alter British politics without even being a Member of Parliament. In short, referenda attempt to represent the people by asking for a simple answer to a complex question.

On the other side, Remainers are keen to emphasise the British tradition of parliamentary democracy. Previously more than willing to delegate power to the undemocratic European Union, paradoxically, many Remainers now find themselves defending parliamentary sovereignty. Liberal Democrats, and various figures within the Labour party, from Owen Smith to David Lammy, have emphasised that the referendum was merely advisory and was not legally binding. Parliamentarians, elected to represent the people, should choose whether to activate Article 50, the assumption being that many would opt against it. Similarly, these Remainers also reserve the right to call a second referendum on Brexit, the idea being that the referendum didn’t reflect the will of the people in the way they wanted, so let’s give it another try. This may appear undemocratic if we follow the logic of direct democracy. Thus, we see that direct democracy and representative democracy are in conflict. Nonetheless, it is worth remembering many ‘Remoaning’ MPs sitting in strong Leave constituencies, Tristram Hunt for example, are flying electoral kamikaze missions. In short, parliament is a machine designed to mediate between the conflicting, contradictory and often contrarian opinions of the general public: a complex (and often unsatisfactory) answer to a complex question.

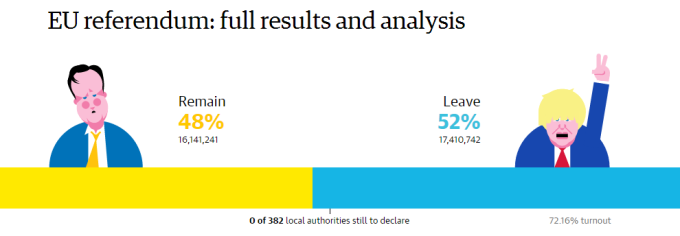

When the referendum was first announced, many on the continent assumed that Britain would set up local forums to debate Brexit. This deliberative form of democracy stresses the importance of informed debate. The idea being to ensure citizens knew what they were talking about, had heard opposing arguments and were in touch with public opinion generally. The basic point is that democracy is a process. Its vital values, like engagement and participation, have to be cultivatedand nurtured. It’s not just, like football, a results game. As the referendum played out, it became clear how foreign this continental idea is to British political culture, where the arena of debate tends to be limited to parliamentary chambers, television studios and the columns of the national press. Without localised forums and deliberations, it is unsurprising that on a national level, the debate was polarised and involved almost no nuance. In such a climate, democratic politics therefore becomes decided by personalities. These personalities tend to be media constructions: the result of good media management and spin doctors. As a result, the referendum campaign was framed in the media as David vs. Boris, the ultimate final decider of a schoolboy rivalry, as The Guardian’s results and analysis coverage exemplifies.

We need some clarity about democracy. We need to move beyond the Brexiteer and Remoaner deadlock. We need to resolve the tension between direct and parliamentary democracy. Democracy is about people power. It is an ongoing process that doesn’t end with the result of an election or referendum. When it comes to Brexit, paradoxically, a European approach is in order. Working out what we want from Brexit will involve talking to each other, not just to our representatives in parliament, but on a local level. Yanis Varoufakis and John McDonnell were on the right lines when they toured Britain, setting up public meetings with space for dissent and discussion, arguing the case for a more radical, democratic Europe. Public engagements such as this need to become more commonplace to inform and politicize people. We need to improve the standard of debate, lift it out of the gutter, before we can get on with doing anything.